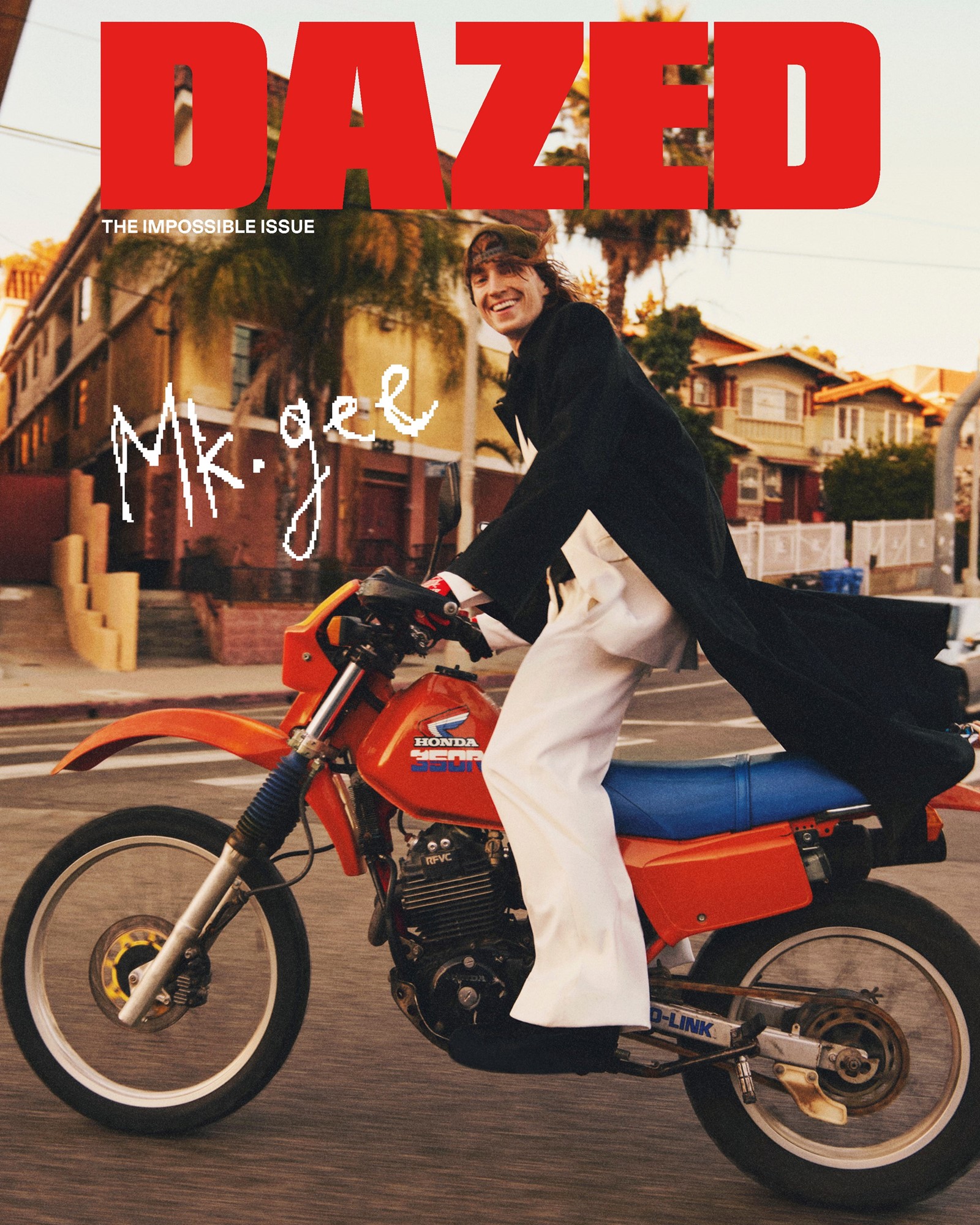

Taken from the autumn 2024 issue of Dazed. Get your copy here.

The miseducation of Mk.gee began with a technological error, a musical discordance. He was nine years old and it was the golden age of pirating, when YouTube-to-MP3 converters reigned supreme and streaming apps had yet to reach their cultural zenith, cornering the listening market and bending it around themselves. Back then, if you were young and curious and without pocket money, you had to familiarise yourself with the arcane science of seeding and torrenting, summon the patience to slowly import files to your iTunes library and then laboriously reorganise all the information: the incorrect titles, the jumbled track listing, the disappeared artwork. LimeWire, Morpheus, DatPiff, The Pirate Bay – these were the clandestine gods of our manic, obsessive times, the great Promethean connectors that siphoned the sublime and sowed legal panic at the RIAA.

Mk.gee, who was born Michael Gordon in 1997, was partial to a software called Pandora. He liked that he could leave it running on his laptop while he was away at school, and come home to find dozens of new songs uploaded, automatically, to his iTunes. “I built the weirdest, most extensive library of music that way,” he tells me. He was reared on The Black Keys and Sly Stone and Bruce Springsteen and Nile Rodgers; every afternoon was like Christmas morning, every song a gift to be unwrapped. The first CD he ever owned was probably something by Deep Purple, who won the Guinness record for loudest pop group following a 1972 show in London that knocked three audience members unconscious, but the first one he bought for himself was The Blueprint. “It really freaked me out,” he says. He remembers importing it to iTunes and hearing Jay-Z luxuriate over those plush, honeyed soul samples, how the diamond clarity of his mogul flow called into question everything the young man had been listening to up until that point. It hadn’t occurred to him that Pandora was compressing all of his music, demoting everything to a low, 12-bit resolution that was murky and indistinct, obliterating the headroom between the peaks and valleys so the songs sounded gauzy as a Cindy Lee transmission.

“The CD was so hi-fi that it was like Jay-Z was actually inside my brain, talking to me,” says Gordon, closing his eyes and bringing his fingers to rest on his temples; I notice a small tattoo of a winged horse between his left thumb and index finger. “That’s probably why I like underwater-sounding things. Because I grew up on 12-bit music.” (Streaming apps now use 16- and 24-bit rates.)

Mk.gee makes music that sounds impressionistic, hypnagogic, fucked up. His synths wobble and flicker and buzz. His drums stutter. His homespun mixes are spiked with weird flyby noises that clang, scrape and echo – here, a laser beam; there, an unsheathed sword – and his chords can be warped or jagged, sometimes downright unpleasant. Take, for example, “Rylee & I”, from his debut album Two Star & the Dream Police, which is built on a mutilated, atonal guitar riff that sounds like it was mastered in a malfunctioning washing machine. Or how the distortion and feed- back on “DNM” gives the impression that a train on the Northern line just screeched past the mic. Or how the languorous, shoegaze-y “Breakthespell”, with its pitched-down vocals and haunted, drowsy atmosphere, sounds telegraphed from the bottom of the ocean. It wasn’t a direct influence, but Gordon was reading a lot about the history of planned obsolescence while making the record, “about how lightbulb manufacturers in the 1930s got together and decided to make worse lightbulbs, because nobody was making any money,” he says. “I like taking cheap, bad gear and trying to make the best song with it, because it forces you to say something interesting and to compensate for poor quality.”

“I just want to be known for making the best music. Not for anything else, really. I’m not trying to sell you anything”

It’s a diffuse, 80s-indebted language that feels native to Mk.gee’s personal sensibility, so singular it has spawned, to the artist’s disdain, a whole ecosystem of Reddit threads and YouTube videos, each chris- tened with various takes on “How Does He Make His Guitar Sound Like That?” The American musician and producer Dijon, whose own debut album, Absolutely, found its ramshackle spirit when Mk.gee started working on it, has said of his friend and collaborator’s guitar playing: “I think he might be creating or transmitting from an alien planet.” An editor for Rolling Stone, awestruck by the sonic and emotional textures that Mk.gee is able to recreate live, described the overall effect of these impressionistic soundscapes as feeling like “a tear opening in the universe”. Even Eric Clapton compared discovering Mk.gee to his first time hearing Prince, Mk.gee’s stated hero, pronouncing that he has “found things to do on the guitar that are like nobody else”.

In conversation, Gordon is prone to long, philosophical digressions and dazzling interludes of self-contradiction. For example, during an exchange about the ways critics write about his blasé, omnivorous approach to genre, he says, “I just want to be known for making the best music. Not for anything else, really. I’m not trying to sell you anything – people have gotta stop selling you their personality, and just make a perfect song. I don’t want to sell you my personality. Categorically, I think people are pretty confused by me, and when you’re confused, you put whatever’s confusing you in a particular box, or zone. And there’s nothing wrong with that if it helps you to understand the music. But categorising me as a good guitar player? I mean, I am a good guitar player; I like to find new cadences and interesting arrangements, and contextualising different stuff on a guitar with weird production choices. But I don’t really relate to the guitar any more. I don’t like its nature... Honestly, guitar is, like, the least interesting thing about the record to me.” When I ask what he thinks the most interesting part of the record is, thinking he’ll reference how he writes songs that sound like fables, he pauses for a full 30 seconds, tightens his lips and then admits, laughing, “OK, OK, I do think it’s interesting.”

There was a time not so long ago when Mk.gee seemed doomed to the status of an artist’s artist, beloved mostly by the rarified few who were hip to his musical experiments and wanted to keep him to themselves for as long as possible. He has rarely done interviews over the years, partly because the demands of the form can frustrate him – the persistent reporter’s hunger for specific meaning where abstract feeling ought to live instead – but also because, plainly, nobody ever seemed interested in interviewing him. Now he’s playing on both Jimmy shows (Fallon, Kimmel) and at Jil Sander runway shows, selling out headlining tours, and making fans of his contemporaries: Miguel, John Mayer, Justin Bieber, Bon Iver (whose tour he opened for in 2022, with Dijon). The comments under his YouTube videos are rammed with people spinning grand unifying theories about the album’s oblique narrative, parsing the tech-y nuances of his bruised guitar playing, comparing him to an angel or a god, and trying to understand why these songs sound both uncannily familiar and still totally new. Six years since Frank Ocean played him on an episode of Blonded Radio, it seems the best-kept secret in indie music, a surefire generational talent, has been released into the air like a genie from a lamp. And he’s intent on doing everything wrong.

New Jersey is not famous, despite its considerable musical pedigree, for its enduring contributions to the evolution of pop. It doesn’t seem to matter that Springsteen and Sinatra and Smith (Patti) are from there, that Yo La Tengo formed in Hoboken and George Clinton straightened hair in Plainfield, or that Lauryn Hill is from there and Whitney is from there and SZA, herself an apostle of Mk.gee, is from there. The whole state lives in the cultural shadow of its rougher, more flamboyant sibling, New York, and Gordon says it has a metaphorical chip on its shoulder as a result. But he loves the people there, perhaps more so than the grinning, ambitious climbers of his new home, Los Angeles, and feels drawn to their “deep, mad sincerity”; the only movie he really watched while making Two Star & the Dream Police is called Wildwood, NJ, a strangely affecting documentary from 1994 about the lives and dreams of several women in the seaside community of the title.

Gordon grew up in a small, south Jersey town called Linwood, where most of the supposedly ‘notable’ people were either athletes or politicians. “It was never considered cool to be doing music when I was growing up,” he says. “There wasn’t really a huge culture for music. There was a respect for music, for sure. But this crazy idea of becoming an artist? That wasn’t really a thing.” Still, he could never manage to shake his affinity, and his dreams at night followed him into his waking life. When he was six, his mother enrolled him for lessons with a Russian classical pianist, whose strange, thick accent he struggled to decipher. The two found a common language in music, though he remembers the recitals as being high-strung and intimidating. A procession of little kids, no older than ten or 11, would waddle up to the bench, plop themselves in front of the grand piano, and tear through ten-minute pieces from all the hot-blooded, serious composers: Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, Schubert. Then Gordon, seven years old and hooked on The Isley Brothers, would meander over and play the two-minute pop ditties he’d written himself, disorienting the crowd of purists.

Since most young people would rather be Hendrix than Beethoven, Gordon decided to trade in the piano for something cooler, something showier, when he was 12. A vapour of frat-boy corniness had already attached itself to the acoustic guitar, made it the province of those who serenaded their girlfriends with songs by Jason Mraz, and so he decided to become a master of the electric. Nile Rodgers played the electric. Jimi played the electric. Clapton, Prince, Sly: all the rock musicians he grew up on, and the blues artists who inspired them (BB King, Muddy Waters), played the electric. Never one to take a straight path, Gordon instead learned the basics from a guy who played the upright bass. “I think it was helpful to do it that way,” he says. “I never liked the idea of getting lessons from a guitar player, and thought it would be more useful to learn from someone who didn’t play the guitar at all – someone who could give musical lessons that were more exploratory, more about trying things out.”

“Why would you not think the most honest thing you can do is to lean into the weirdness of the times, and make things that don’t make any sense?”

His grandparents ran a jazz society out in Somers Point on the Jersey Shore, where they held work- shops, masterclasses and lectures on pioneers of the genre, like Coltrane and Getz. Occasionally they invited artists to play small shows for a few hundred people, and Gordon recalls a performance from the great jazz guitarist Pat Martino, who held his pick the way one holds a champagne flute, pinky extended in politesse. As a young teenager, Gordon formed a jazz trio with two of his older friends, the only other kids around who were serious about music, and they started gigging in bars along the shore where they were all too young to drink. The germinating instincts of a young virtuoso are already present in the videos from that time; during a rock show in Florida, the 15-year-old Gordon travels across the stage with a wide, impish grin on his face, shredding the guitar from behind his back.

But to hear Gordon tell it is to get the impression that you’re watching a scene from Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues; the whole history of music, after all, is basically a story of clashing, incurable egos. Tension in the trio set in when the other members refused to take seriously his creative ideas. “I just wanted to write songs, man, I just wanted to be the best,” he says. The atmosphere began to feel stultifying. “I always knew that I wanted something more, you know, because I wanted to be the best ever. And so eventually, as one does, I got a four-track recorder. And then I was just like, ‘All right, fuck y’all, I can play your instruments even better than you can. I’m just gonna learn how to record myself.’” He was already an expressive guitar player, and comfortable on the piano, so he started messing around until he became a multi-instrumentalist. (Though Andrew Sarlo helped him with arranging some of the songs, and Dijon contributed some production, all the rest is Mk.gee.) “And then they were terrible, of course, the demos I was making,” he laughs. “But that was how I initially got into recording.”

Gordon moved to Los Angeles when he was 18 and enrolled at USC Thornton School of Music, widely considered to be one of the best music schools in the US. The popular music programme he selected is one of the few music degrees in the country that focuses on an amalgam of rock, pop, R&B, folk, Latin and country, where most others cater to classical or jazz musicians specifically. Outside of his classes, Gordon thought he might try his hand gigging as a tour guitarist. It didn’t work out. “I don’t think I was suited for the specific style of playing they were looking for,” he admits gingerly. “It was a lot of plug-and-play with these fucking corny songwriters, but that was just what I had to do at the time.” He got fired a lot, because the way he played the guitar was odd; he’d grown accustomed to leaning into his idiosyncrasies while playing on his own, and didn’t want to adapt to fit around other people.

In his freshman year, he met a guy who gave him a cracked copy of Ableton, which he used to record and produce a suite of woozy, funky songs with the help of some classmates. He released it in 2016 under the title 8ams, dropping out of uni around the same time. His singing here is tepid, the instrumentation a bit washed out, but some of the riffs betray flashes of songs he would release later on: Gordon is surprised when I mention it. “We live in such postmodern times where you just have the ability to find these blueprints from when I was learning, in real time, how to actually make a song,” he says. “I was really just experimenting, trying on different hats, different guys. I would make stuff quickly in my bedroom and put it out. And then I’d be like, ‘I can’t believe I made that’ – that was the only reason to make things back then. That instinct is still there. It’s why I like to make things fast. The faster you make things, the less time you have to think, and the more likely it is that you’ll capture the spirit of whatever it is you want to come through.”

He released Pronounced McGee in 2018, a groovy, sun-bleached “double EP” that he made in his bedroom, grounded in the beach rock, psych-funk and late-70s R&B of his adolescence. One of the songs, “You”, ended up on an episode of Frank Ocean’s Blonded Radio, and brought a whole new fanbase to Gordon’s gradually mutating sound. Six months later, he released another EP called Fool, a cloudy collection of acoustic guitar-based songs that sound nothing like an acoustic guitar. A Museum of Contradiction, his 2020 mixtape released under IAMSOUND and Interscope, abstracted his sound even more, plunging it further into leftfield instrumental psychedelia. Many artists start out weird and experimental, then pivot the songs to achieve more commercial appeal, slipping them into ironed, buttoned-up suits. Gordon has done exactly the opposite. He considers Two Star & the Dream Police to be his first real album. Everything that came before was practice, an exercise in drafting a new language in public.

“I think people are scared to make mistakes and release projects where they’re just trying things out because it’s all forever – because it lives online and can be seen and interacted with so long after you’ve moved on from it,” he says. “And so there’s a fear to try things out. I’m not really scared to try stuff. Everything I’ve ever done is already out there, and I didn’t know how to do anything when I started. Because of that, I have no fear going forward. All my cards are out on the table.”

“I like taking cheap, bad gear and trying to make the best song with it, because it forces you to say something interesting”

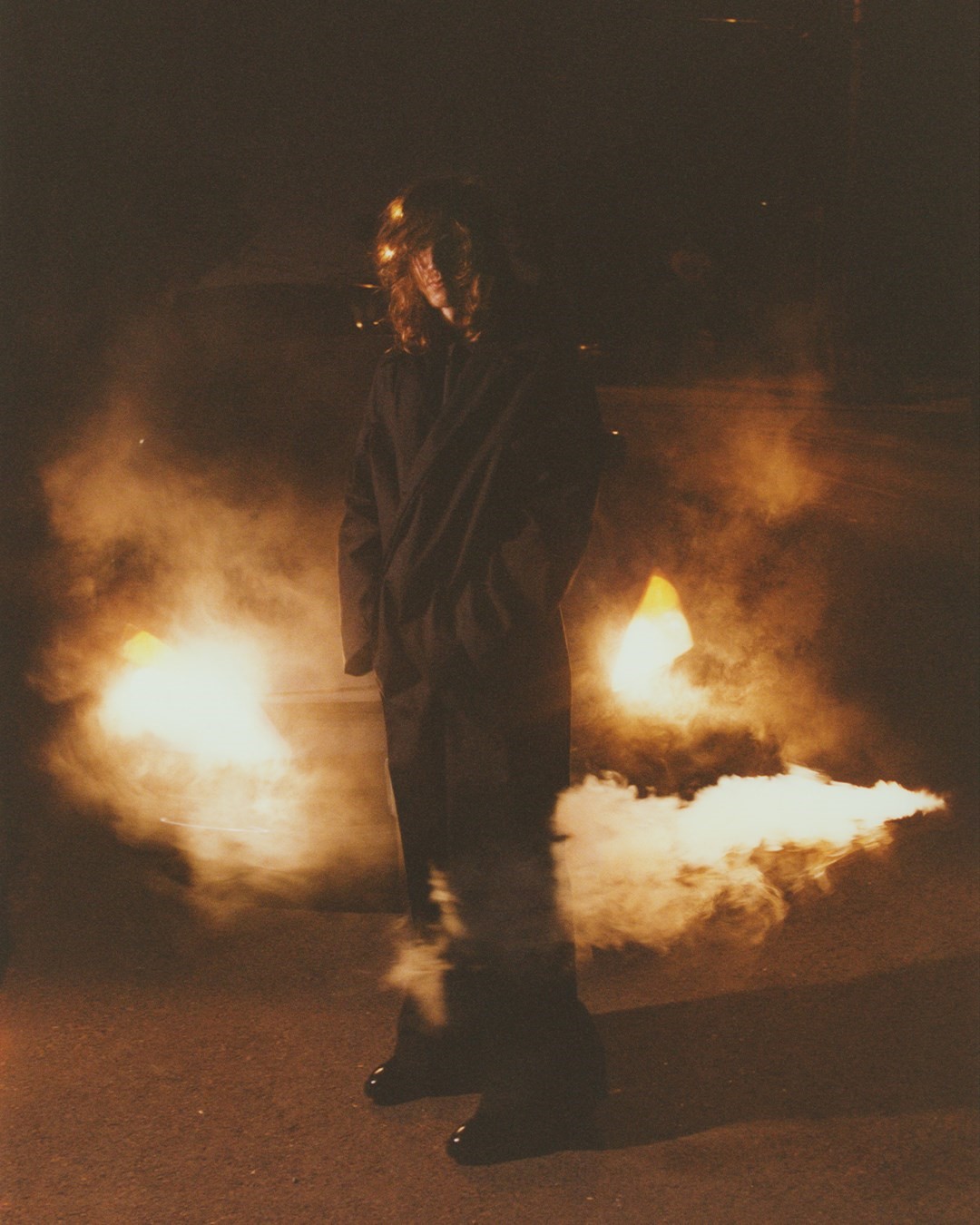

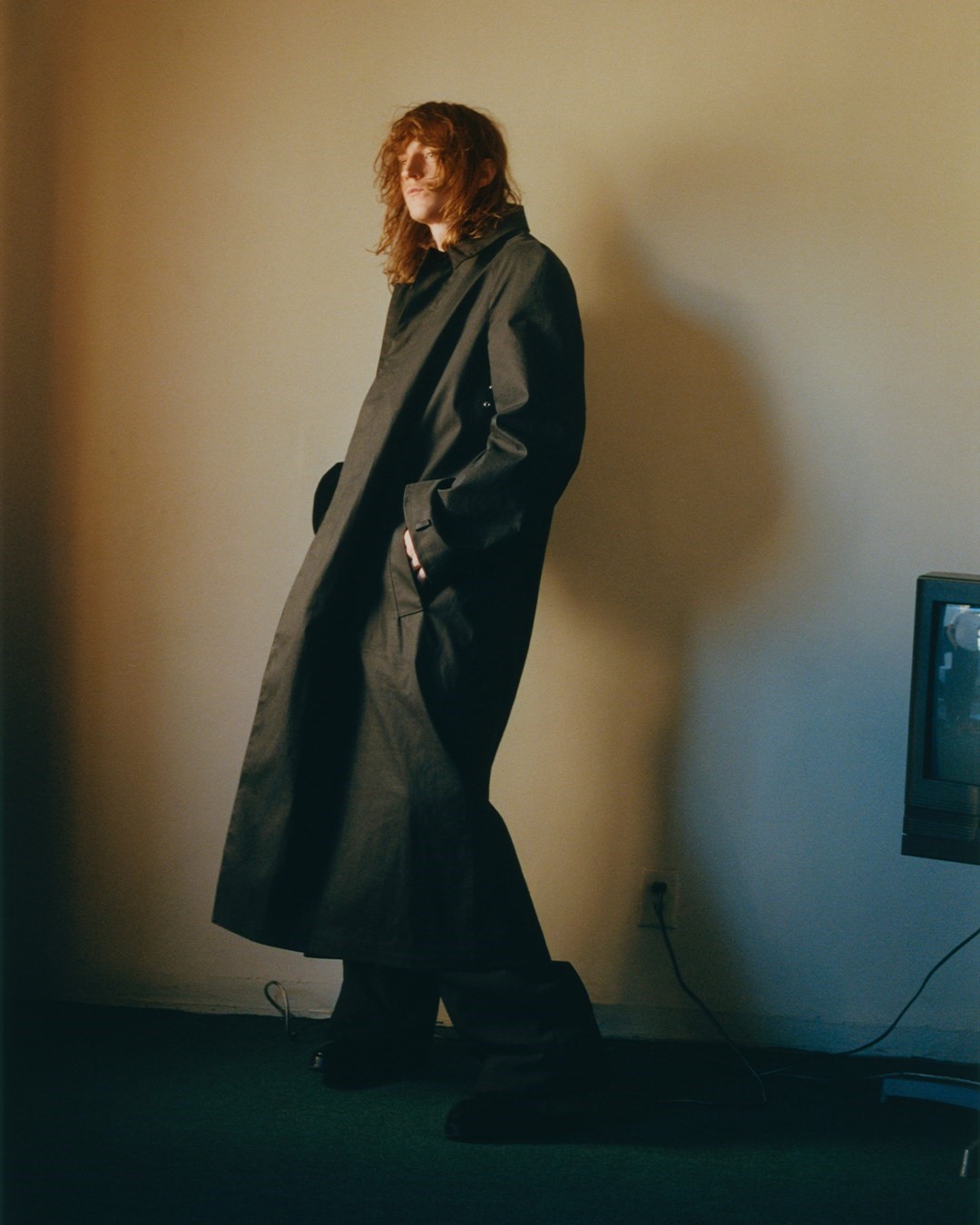

It’s dark at the concert theatre in Toronto. A smoky shaft of light wreaths the artist and his gleaming Fender Jaguar, a reissue from the 1960s, in a gauzy, silvery halo. Sometimes the mood changes, the light shifts, one pale beam of white light appears to emanate from straight out of his chest, and Mk.gee at once resembles the eldritch character of his album cover – like some wearied messiah, some embattled hero on furlough from a myth, or dream, or apocalypse. He’s dressed casually, in a T-shirt and cargos. He says next to nothing. His eyes, his expressions, are obscured by a tangle of wild brown hair, but sometimes, as when the audience jubilantly sings his lyrics back to him, he might break into a grin, not unlike that 15-year-old’s grin in those old recordings, and then shred a glittering, discordant guitar solo that brings the room to a standstill. He makes the guitar sing, and weep, and shriek; in his hands it can be a snare, or a drum, or a second singer. The band (Zack Sekoff and Andrew Aged) melts each song into the next, improvising so the songs end but continue on for several minutes longer than they should, as if they could go on forever.

Gordon sold out the tour this year, and he’s already preparing for another one. He has plans

to release new music this autumn, but he is cagey about exactly what, and when. Four years passed between the release of A Museum of Contradiction and Two Star & the Dream Police, during which he was producing for Dijon, The Kid Laroi and Charlotte Day Wilson (he has a credit on Drake’s “Fair Trade”, which samples Wilson’s “Mountains”). “It’s not like I took time off,” he says. “I was just like, ‘I’m not going to reemerge into the world until I’m the best at some- thing indescribable.’” It seems unlikely he’ll go so long without releasing music again – particularly because perfection is anathema to his craft. He’s interested, for example, in the trajectory of Prince’s career, how his gear upgraded after the first two sparkling pop records but the songs only got weirder after that. “For him, it was always about the sentence, not just the individual songs, and being down to go all the way and try things out. He did make, on some of the best records ever, really bad songs.” (Dirty Mind is his favourite Prince album.)

“For me, as time goes on, I don’t want things to sound better,” Gordon continues. “I don’t want it to sound like I’ve been tweaking a bass drum for four weeks. That’s not what music is to me. I want the spirit to get much larger. And the idea is just to become crazier. Because if you have the spirit, then you can pull anything off, and the ideas will get stranger.”

He uses that word, spirit, some 30 times over the course of our three-hour conversation, then apologises for returning to it. But there’s something fitting about the term that captures the ineffable quality of these songs, their refusal to autocorrect to something cleaner, more legible. He makes reference to the “explosive freedom” and “huge spirit” of the 33-minute Two Star & the Dream Police, which was originally much longer, and how he pared everything back because he “wanted every song to feel like a speeding bullet”. He praises the inspired “spirit” of Eric Dolphy’s extemporised jazz solos and extended techniques, how his chromatic approach to tonality could obliterate the logic of a pretty harmony and make it ominous, haunted, angular, in ways that “opened the door” for Mk.gee’s own experimentations. He notes the ways most people misunderstand pop music as a genre rather than a “true, undeniable spirit”, and references how Sinéad O’Connor couched “alien melodic choices and cadences” in the language of pop – not unlike how he approaches his songs, “writing pop tunes over weird, fucked-up productions and acting like it’s not happening, just to gaslight you a little bit”. It goes without saying that Gordon is a student of music history, adept at blending his varied influences without ever sounding too much like them; he considers formal song structures only so he can abandon or ruin them.

“I’m not really afraid to not make sense, or to not be relatable,” he says. “It sounds corny, but the world is fucking weird, man. It doesn’t make sense. And if somebody is telling me that it does, then I probably can’t trust them.” It sounds like that thing O’Connor once said online, about how being well-adjusted in a profoundly sick society is no good measure of health. “Why would you not think the most honest thing you can do is to lean into the weirdness of the times, and make things that don’t make any sense?” he says. “I’m not saying that the new record doesn’t make sense. But as a catalyst, I think that’s really important to me.” He pauses. “Maybe making sense is overrated.”

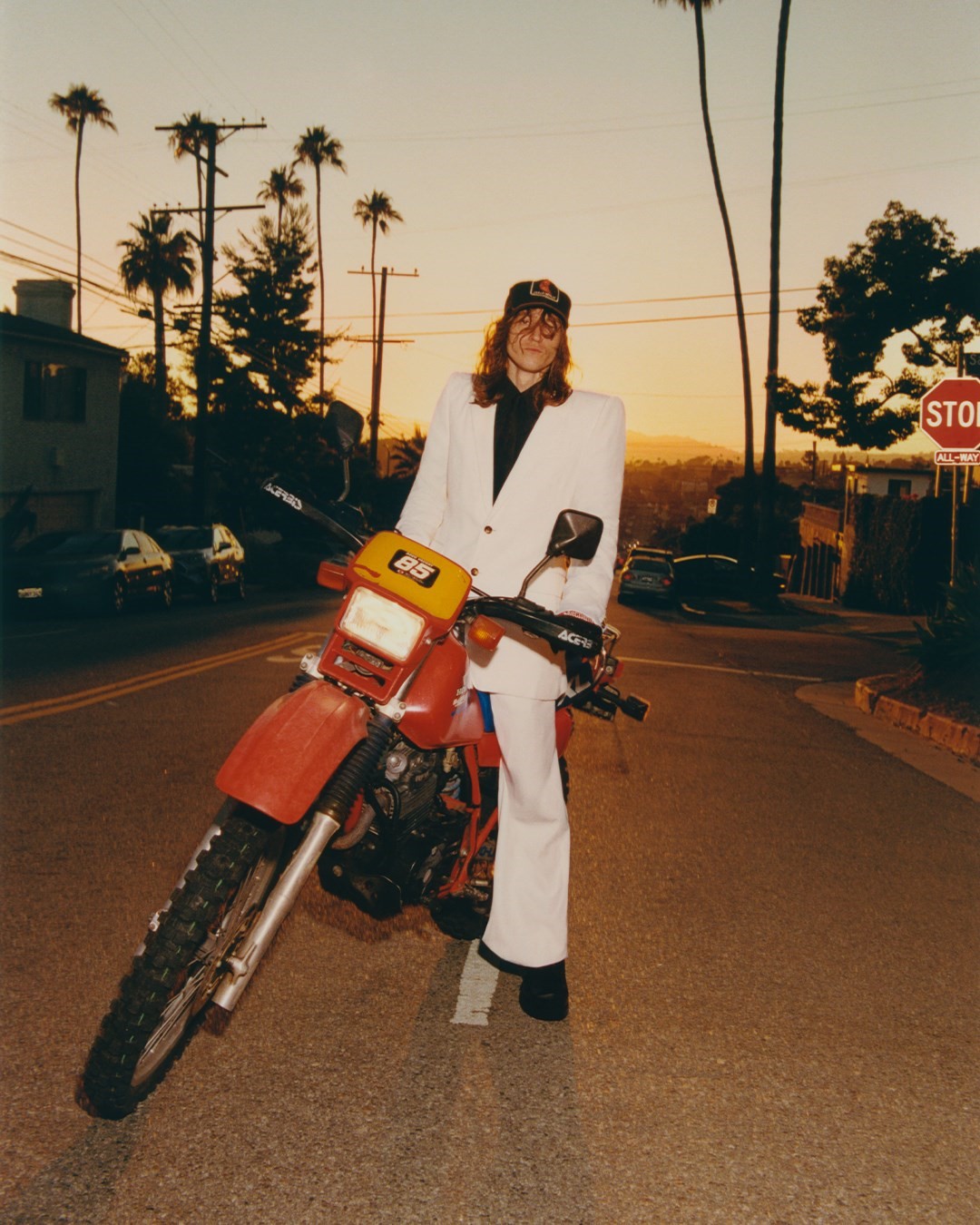

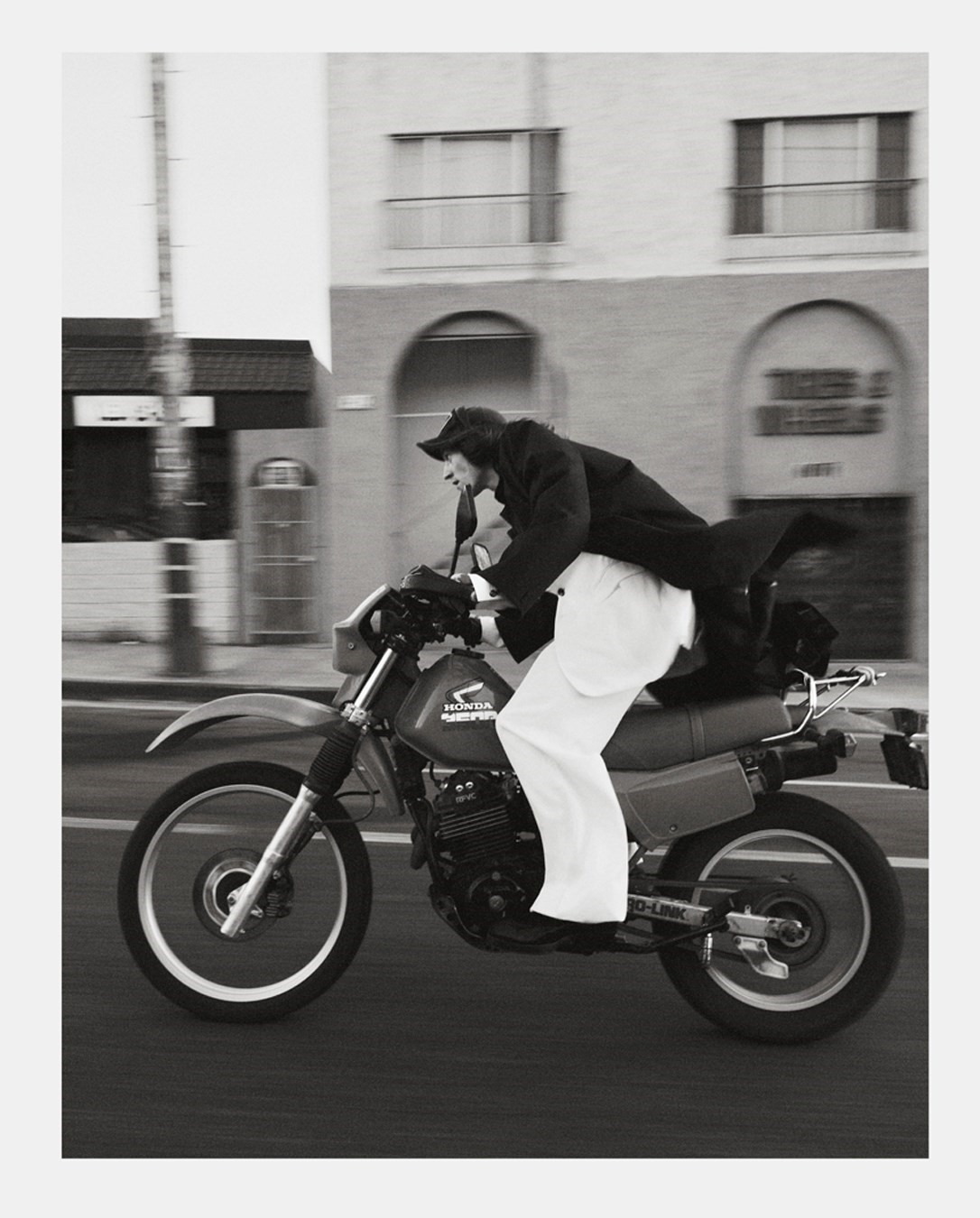

Grooming JOHN MCKAY at FRANK REPS using DIOR BEAUTY, photographic assistants PABLO CALDÉRON-SANTIAGO, ANNABEL SNOXALL, styling assistants ANDRA-AMELIA BUHAI, LEA ZÖLLER, TARA BOYETTE, ANNA HERMO, RANDY MOLINA, MIRIAM RUVALCABA, production RACHAEL EVANS at REPRO, production manager ERIN SHANAHAN, production assistants MAX CASTRO, CHYLLE DIGNADICE, ARIEL CARILLO, GARRETT CHARBONEAU

The autumn 2024 issue of Dazed is out internationally on September 12.