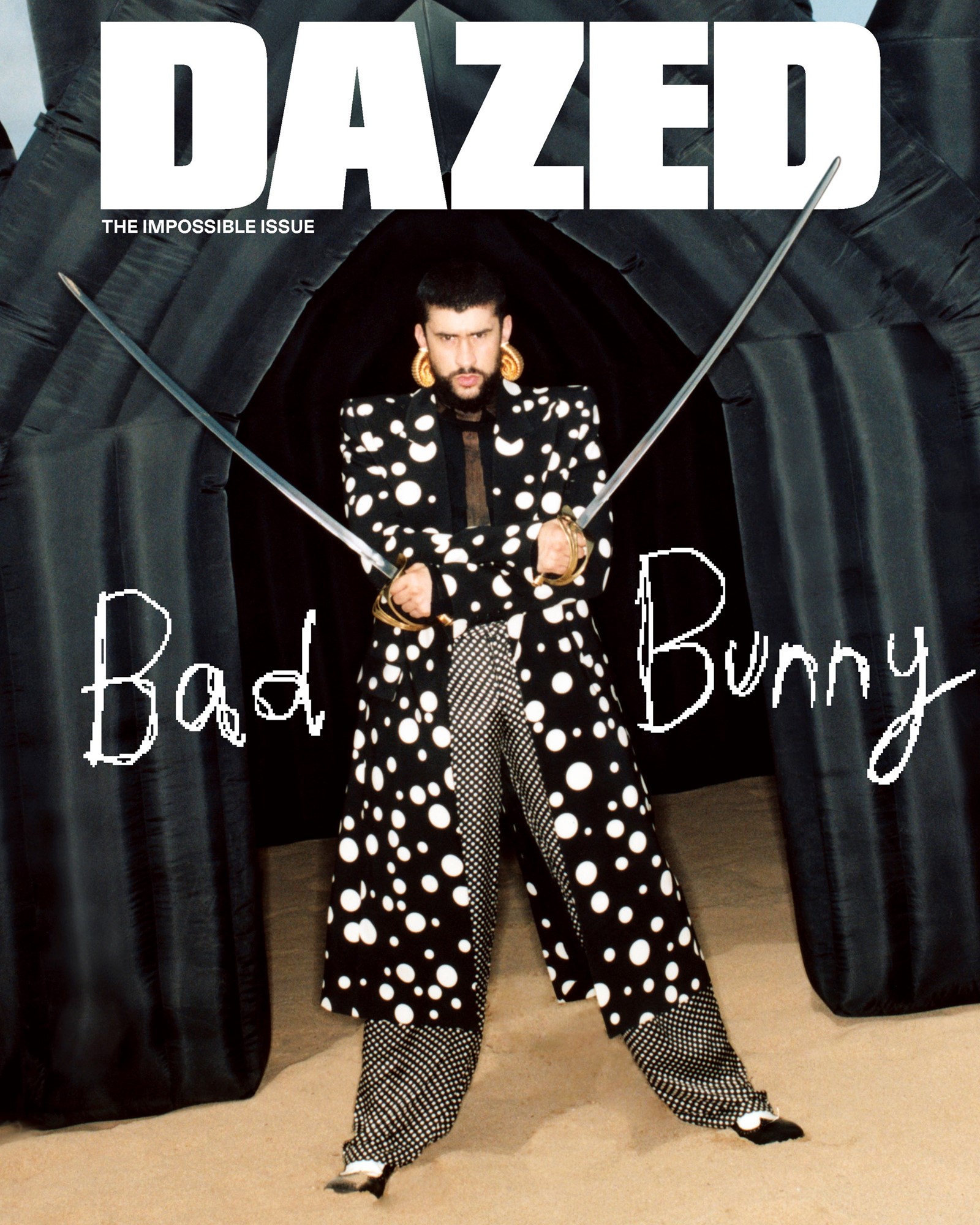

Taken from the autumn 2024 issue of Dazed. Get your copy here.

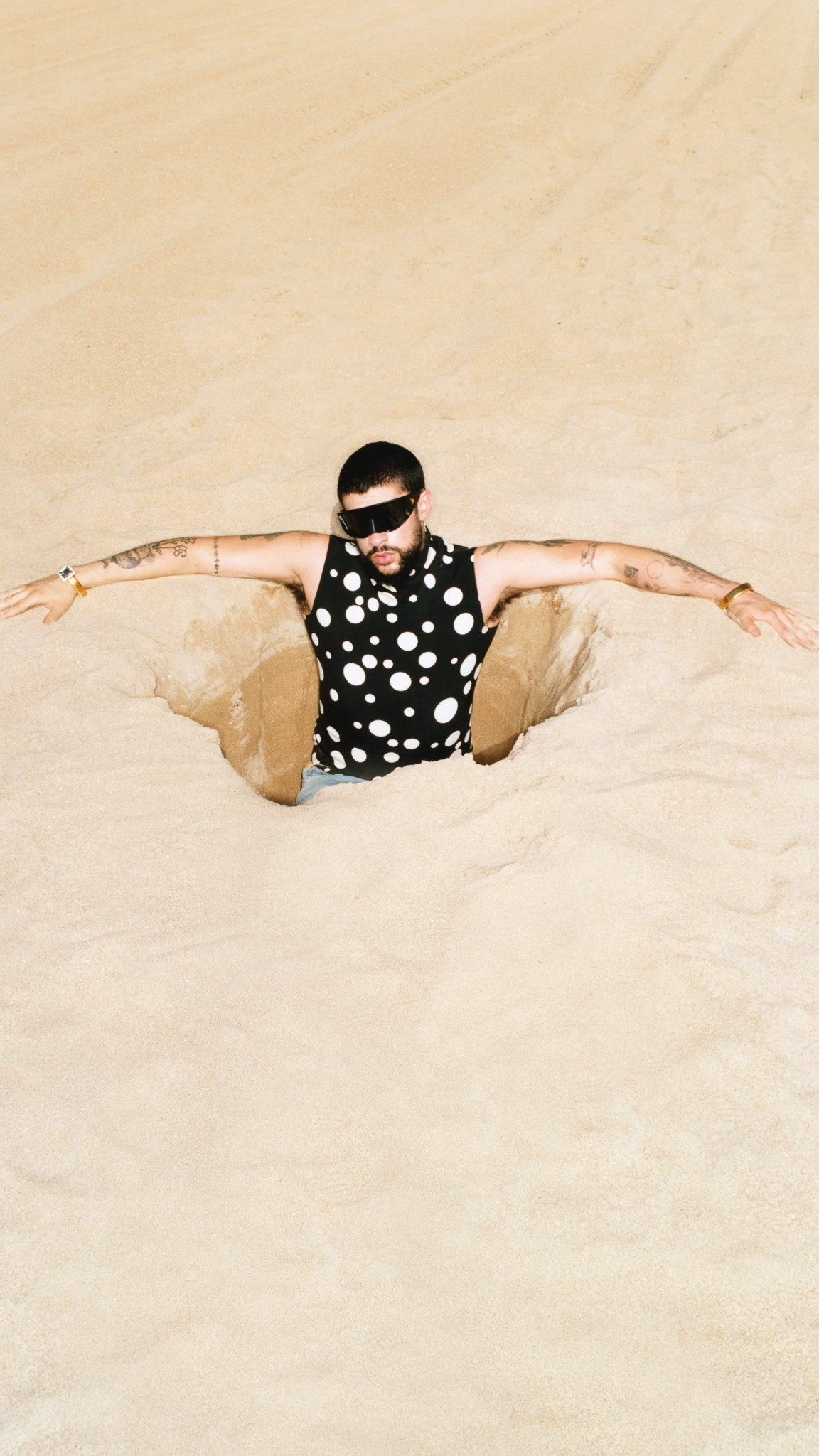

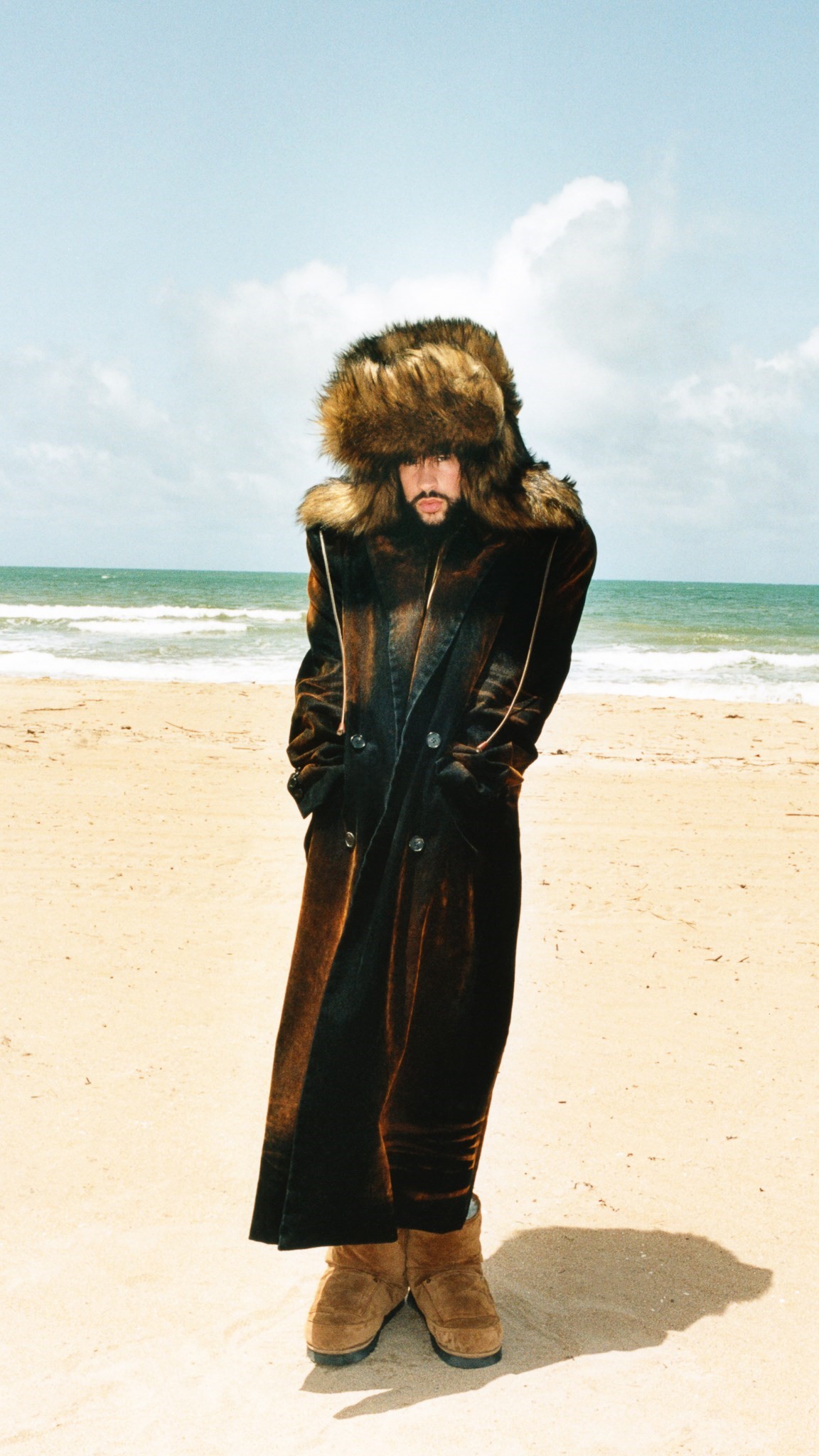

It recently occurred to Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, amid the blistering humidity of a Puerto Rican summer, that he perhaps didn’t know as much as he should about his family history and, by association, himself. Martínez, who records under the musical moniker Bad Bunny, had recently wrapped up a breakneck year – touring North America, dropping a near-90-minute-long new album and performing at Vogue World in Paris – when he decided to return to the Caribbean island where he’d grown up. He needed to take a beat. But during those sun-dappled afternoons spent lounging on the beach, Martínez’s thoughts began drifting backwards – and quite literally, when our call connects. “I’ve been looking a lot at my surroundings behind me,” says Martínez, gesturing at the San Juan coastline over his shoulder. But lately that impulse has begun transforming into something deeper.

Martínez’s boyhood brims with memories of skateboarding, making mixtapes and swimming in the Cibuco river that bends through Vega Baja, a rural enclave located a bumpy 45 minutes from San Juan. But what had his ancestors’ lives been like? What circumstances led them to plant roots in that exact place all those years ago? “I have these chats with my family members about the old days, and [learning] what their upbringings were like, what my grandfather’s upbringing was like,” he says, brushing back his shortish mop of brown curls before carefully placing a straw hat atop his head. “I’m on that wave. Trying to imagine what my life would have been like then.”

Excavating those bygone days seems like an unexpected heel-turn for Martínez, an idiosyncratic Latin trap singer who’s made a career out of lurching towards the future. On the surface, his musical oeuvre suggests a hyperfixation with the days and years to come, no matter how grim or promising they might seem. When the world shuttered indefinitely in 2020, for instance, Martínez responded with El Último Tour Del Mundo, a concept album that unpacked what the final tour on a post-apocalyptic Earth might feel like through a series of urgent club bangers and throttling rock jams. “No Me Quiero Casar” (“I Don’t Want to Get Married”), a single from his latest album Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, centres on how Martínez’s imminent prospects – romantic, financial and otherwise – look so rosy that he feels averse to the usual trappings of adulthood: calmness, maturity and, yes, marriage. (He happily predicts in the song that in 2026 he will still be single.) Over a beat that is by turns menacing and buoyant, and interspersed with samples from reggaeton forebears such as Tego Calderón and Frankie Boy, Martínez goes on to rap, in his signature lilting warble, that “mi futuro tengo que cambiarlo hoy” – meaning that “I have to change my future today”.

Yet hovering just beneath his success lies a vulnerability that’s rare in bravado-laden reggaeton and Latin trap circles. In fact, some of Bad Bunny’s songs may even have you convinced he’s unsure of everything and everyone, particularly himself. It’s especially striking on “RLNDT”, a song from his 2018 debut album X 100PRE, which draws on the true story of four-year-old Roland ‘Rolandito’ Salas Jusino, who vanished from a Puerto Rican park in 1999. Over a downtempo trap beat, Martínez conjures a psychic connection between his personal aimlessness and Jusino’s disappearance, when he cries out: “Hola, ¿quién soy? No sé, se me olvidó.” (“Hi, who am I? I don’t know, I forgot.”) Practically gasping, Martínez wails about losing the “GPS” in the middle of his journey, unsure now how to “navigate with this darkness”. Then there was “TRELLAS”, a cosmic alt-rock ballad from 2020 recalling Mazzy Star by way of late Argentine songwriter Gustavo Cerati. In it, Martínez wrenchingly croons about being lost despite gazing up at the stars: “Y me pregunté si habrá alguien para mí / Quizás en otra galaxia lejos de aquí.” (“And I asked myself if there might be someone for me / Maybe in another galaxy far away from here.”) Daddy Yankee doesn’t ache, at least not visibly, like Bad Bunny aches.

Varied as his work might appear in scope and style – from moody pop-punk to boogaloo and beyond, his baritone vocals morphing with the music – Bad Bunny often drifts back to the same question in his lyrics: Why am I the way I am? It’s a thematic concern that, alongside a recent move to Los Angeles, sheds light on the artist’s increasingly forensic interest in his lineage.

When I ask Martínez if he finds it challenging to relax during this pause in Puerto Rico, he cryptically replies: “That question you’re asking me is pretty unstable.” He then proffers an example: sometimes, when he comes back to Puerto Rico after a lengthy tour, he feels guilty lying on the couch even for a day. “‘But motherfucker, you finished a tour!’” he exclaims, gesturing to himself. “‘Rest, put on a show, do nothing. Look out the window.’ But that mentality I have to always be doing something, to always be producing...” he trails off. “I think it’s more because my mind is always looking for something to do.”

Since late 2016, when he dropped his first single “Diles” on Soundcloud, Martínez’s star has risen at such an improbable clip that more than one college course is now dedicated to studying how he managed to pull it off. To date, he’s notched chart-topping collaborations with Ozuna, Cardi B, Rauw Alejandro, Tainy, Arcángel and J Balvin among dozens of other artists, and his fourth studio LP, Un Verano Sin Ti, became the world’s most-streamed album of all time on Spotify in 2023. The successes of 90s pop stars like Shakira and Enrique Iglesias are explained, at least partly, by their decision to sing in both Spanish and English, two of the world’s most spoken languages. Conversely and somewhat radically, Martínez has yet to record a song in English and last year became the first Latin artist to host and perform on Saturday Night Live since Cuban star Desi Arnaz in 1976.

“When a person is a dreamer, they never stop dreaming. With the time I’m on this Earth I’m going to do something” – Bad Bunny

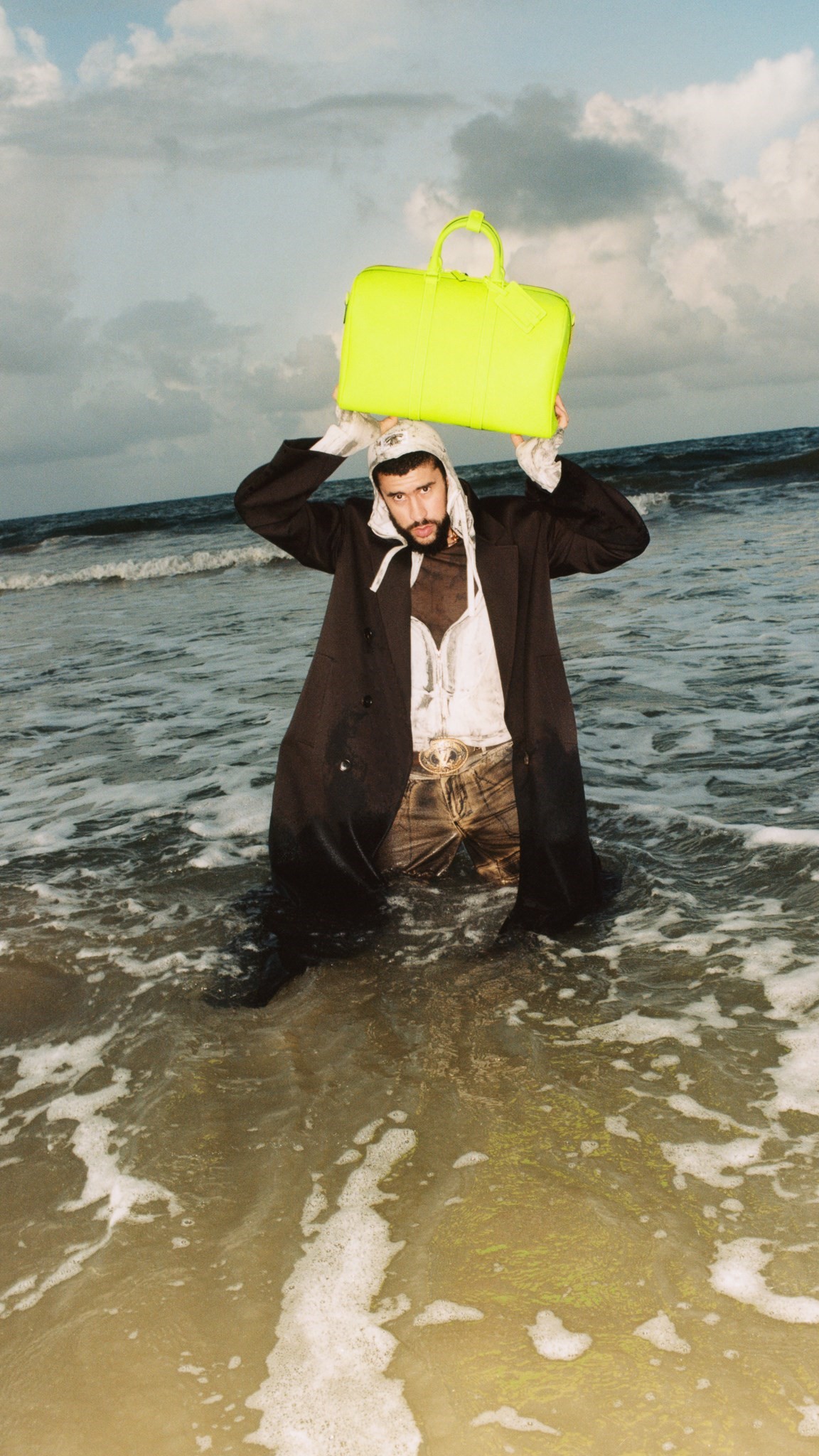

Martínez likes to namecheck his accomplishments in his lyrics, often as a jab to his haters – but in conversation, he’s much more polite about his career trajectory. “I just turned 30 – I can say I’m old, I can say I’m young,” he laughs. “If I look back now I can say I’ve done everything, but if I look to the future I haven’t done anything.” More recently, Martínez has begun moving into fashion, releasing his own adidas trainer and co-hosting this year’s Met Gala while gussied up in a Maison Margiela corset by John Galliano. A clothes-horse who occasionally dons bright nail polish and skirts if he’s feeling it, Martínez once suited up in red leather drag in the music video for “Yo Perreo Sola” – his ode, he explains, to women who relish dancing joyously alone at the club.

Martínez’s penchant for provocation has also garnered no shortage of controversy. Eschewing traditional markers of masculinity, his role in last year’s queer wrestling drama Cassandro, in which he shared a passionate kiss with Gael García Bernal, sparked accusations of queerbaiting. (When asked by Vanity Fair last year how these more femme-leaning sartorial decisions factored into his identity, Martínez reasoned: “You do it because you want to and it makes you feel good.” Martínez has also indicated that he’s sexually fluid in the past.) His frank rapping about coitus and his own anatomy, which he likens in appearance to the kids’ TV show character Caillou, has also raised eyebrows. “Maybe my music isn’t wholesome / But I didn’t invent sex nor marijuana,” he clapped back to his critics in the explosive single “Baticano”. Raquel Berrios, a fellow Boricua (Puerto Rican) musician and frontwoman with Bad Bunny collaborators Buscabulla, says he was polarising from the moment he stepped on to the island’s reggaeton and trap scenes eight years ago. “Everybody felt strongly about him, which was probably a good sign,” she says. “It’s like Björk: You either love her or you hate her.”

Born in 1994 to a truck driver father and a teacher mother, Martínez was a bit of a handful as a child growing up on the island. “I was low-key out in the world. In my house I was more naughty,” he says, laughing. “I was the biggest headache for my mom [out] of me and my two brothers, because I always liked to do things, to invent.” As the eldest child, he kept up good grades but felt continuously pulled towards more imaginative pursuits. In school, he would do things like drum on the desk to make beats, and he sang in the Catholic church choir.

While he has long performed in public spaces – he turned out a cover of “Mala Gente” by Colombian songwriter Juanes in a middle school talent show – the thought of it terrified him as a kid. “I was really scared,” he says. “The moment I had to perform like that, my hands would sweat. When I finished I felt

an indescribable relief.” Nonetheless, he kept getting up on stage, a form of exposure therapy he says helped quell his nerves. “‘OK, Benito, if you want to achieve this, you have to do it,’” he used to tell himself. “‘You have to break with that fear.’”

As a teenager, Martínez liked to stay up all night in his bedroom making beats. Galvanised at once by reggaetoneros and salsero Héctor Lavoe, he started unspooling cheeky freestyles and recording reggae- ton jams with friends. When he was 14, he started scribbling down ideas in a little notebook, pouring his melancholy feelings into song. “I was, as they say, a ‘sadboy’,” he recalls. “I don’t remember the first song that I wrote, but I’m sure it had to do with stories that were a little sad, and heartbreak.”

Martínez kept writing, freestyling and recording music in college, where he was studying commu- nication. While bagging groceries at the Econo supermarket one day in 2016, he noticed that one

of his songs, the raunchy “Diles”, had taken off on Soundcloud; later that year, he signed a record deal. From there he kept dropping songs, often revolving around flashy cars and favourite sex positions as he growled his signature catchphrase, “ey, ey”. When he dropped X 100PRE with zero notice on Christmas Eve 2018, days later partygoers around the world were already scream-singing the tape’s refrain, “Pásame la hookah!” (pass me the hookah).

“If I look back now I can say I’ve done everything, but if I look to the future I haven’t done anything” – Bad Bunny

Beyond exploring the minutiae of love and what goes on in his boudoir, Martínez makes a point to shout out his homeland, at once through overt lyrical nods and on a more subconscious level. Martínez melodically coos in his songs and pronounces most of his ‘r’s as ‘l’s – a hallmark of Puerto Rican Spanish, one that’s sometimes derided by other Spanish speakers throughout the Latino diaspora. His intona- tions have since inspired a new microgenre of artists and listeners to learn to speak the way he does; this summer, the New York Times even declared that “everyone wants to sound like Bad Bunny”.

Martínez has also more pointedly spoken out about the lack of resources and infrastructure that Puerto Ricans often face, particularly in the wake of the cataclysmic Hurricane Maria in 2017. Two years after that, he cancelled his world tour to join ongoing rallies in Puerto Rico demanding that former governor Ricardo Rosselló step down, and recorded the pro- test song “Afilando Los Cuchillos” (“Sharpening the Knives”). Un Verano Sin Ti, his most popular album by a wide margin, peaks with “El Apagón”, a throttling love letter to Puerto Rico that doubles as a send-up to the shoddy condition of roads and the frequent blackouts that often stymie people’s lives there. The song was accompanied by a documentary about how the government has cast aside the needs of its longtime residents in lieu of outside investors with their eyes on tax exemptions.

That impact, however good, hardly means that Martínez is inured from all criticism surrounding issues of identity with his fans. “El Apagón” features a scathing line about how “everyone wants to be Latino, but they’re missing flavour” – which he wrote as a response to certain people only flexing their Latino identity when it suits them. He also drew scorn last year when a fan in the Dominican Republic approached him and put her phone up to his face to take a photo. He threw it in the water. “I’m working on this,” he says of his temper, “but I’m also learning to understand some of the reactions that people have with me.” He’s better able, he tells me today, to navigate the thornier parts of fame. “I’ve learned to accept it and embrace it.”

Martínez wants to keep shapeshifting as an artist, and that might involve more acting – he had roles in Brad Pitt action flick Bullet Train and Netflix crime show Narcos: Mexico recently, plus an unexpectedly silly turn as Shrek for an SNL performance. The child in him still finds the prospect of doing things live, like SNL and his recent Paris Vogue performance, rattling. It leaves no room for self-doubt, which is precisely why he intends to do more of it. “It’s a different kind of adrenaline,” he says, as our conversation begins to wind down. “It’s nerves, but it’s good. It makes you act in a certain way, like firing on all cylinders.”

Martínez makes no mention of a potential new album. The only thing on the horizon, it seems, involves mining the genealogical past he’s so captivated by these days. Through knowing more about his Puerto Rican heritage, he wants to ground himself with insights on “why we’re here [and] where we can go,” he says. It’s entirely possible that these recent findings could wend themselves into his future songs, too, given how generative and “inspiring” he’s found these chats with family to be. That itself has been another sort of achievement. “There’s always a new goal,” says Martínez. “When a person is a dreamer, they never stop dreaming. With the time I’m on this Earth, I’m going to do something.”

Hair TOPHER, grooming YBELKA HURTADO, nails TAI ROSA, set design NICHOLAS DES JARDINS at STREETERS, SFX artist TOMOYA NAKAGAWA at VANITY PROJECTS, lighting MAX WILBUR, photographic assistants STEFY LIN, SAUL CEDEÑO, styling assistants MASZIA OETTGEN, ANA RAMIREZ, RUAIRI HORAN, tailoring JULIO LIZ, set design assistants JEANKARLOS CRUZ, JUANY COCA, digital operator QUIQUE CABANILLAS, executive production STEPHANIE BARGAS at 360PM, production MICHAELA MCMAHON-DUNPHY at 360PM, local production POOL CREATIVE, production assistants JAVI DURAN, NICO AROVIRA, special thanks PHIL GRACE

The autumn 2024 issue of Dazed is out internationally on September 12. Get your copy here.